Right now: in this present moment, my memories have transported me back to Joal. I am reporting to you live from Joal. Seereer village in Senegal. Mostly Chrisitian population in a predominantly Muslim country. We visit this place because it is an anomaly—a rarity. This is one of the only communities in Senegal (a predominantly Muslim country) that have pigs ready to be killed, prepared, and enjoyed.

Here I am. A Christian ? What do these identities even mean in such a religious place? During my time here, I do not think I have prayed once. I thank the Lord, but I say Alhumdillialay. I thank Allah. I hope for things in the will of Allah. Titles and labels immensely separate us from the unidentifiable elements that define us. I suspended these titles and seized every opportunity to lean into spirituality. The fresh moments when the spirit takes over allowed me to pen the following:

To be buried amongst the other.

We visited a space. A burial site. Dedicated at first to Christians. Catholics. Overtime, more bodies began to be buried here. Muslim bodies. Harmoniously buried there, but still an obvious separation is what I witnessed. There is only a finite amount of space. One student asked if the community of Muslims and Christians (who peacefully live together) were still allowing new bodies to be buried. Apparently, the community is still making space for the dead. Willing and open.

I repeat, there is a finite amount of space. The burial site is located on an island, with a bridge connecting to it. As time progresses, the burial site is sure to be filled. Who gets priority for such space ? Who lays claim to the land ? Although Joal is majority Christian, will Muslims still be buried there when maximum capacity is nearly reached ?

Titles and labels immensely separate us from the unidentifiable elements that define us.

The larger question still remains: what does it mean to be buried amongst the other ? Laying next to the other. Ceremoniously so. Still with a distance. How can I lay next to you if I am not next to you. We create such a distance from one another in life and in death. The things we want to be close to, we may never ever get too close to. Why ? There is and will always be a distance. Imagine if we experienced the deepest parts of one another in the most vulnerable ways. I want to tell the truth. I want to speak to, with, and through my heart. I want to eliminate the distance that comes from audio streams, vocality, touch, smell, taste, and hearing. I want that “you know what I mean” kind of distance.

Again, I ask, what does it mean to be buried amongst the other. Sharing the same space where we both ascend to separate heights. Even in death, we will be separate: ascending to our different Gods. I am your other and your are mines. I want to be your other and I want you to be mines. I need you to be my other and I need you to be mines. I want you. I need you. What is black without white ? What is white without white ? I need you in order to understand myself and become the person that I need to become. I need you in my life. And I need you in my death. You make sense of my becoming and my ending. You are the period to my sentence. You are the capitalization to the start of my sentence.

What if we started to see each other in this light. What if we bury ourselves amongst the other ? What if we bury ourselves in each other ? What if we carry each other in the deepest of ways ? I want you to carry me until I cannot carry myself anymore. Teach me how to carry myself, so I can learn a new way. I need to carry you, also, in these same ways. Carry you with the understanding that I am already buried inside of you. I want to carry you knowing that in you is me. In turn, by carrying you I am making the conscious decision to carry myself.

What if I am too heavy ? What if I take up too much space ? The island is finitely limited. But it is surrounded by an infinite amount of water. The depths to which I am able to carry you is unlimited because I know that you take me in you. I would never take up too much space in you. I am not too heavy because in you is light, both shining and a definition of airiness. I fear not of what I am, will be, was, and will continue to be, because in you is fertile for my evolution. I choose not to be here, but here we are, buried amongst one another.

I choose not to believe in the idea of the other. Not because there are other ways of knowing, but because we exist as the other. To be buried amongst the other is to put death to oneself so that the other can live.

We lay witness to each other.

We die amongst the other.

We surround ourselves by the other.

We are each other.

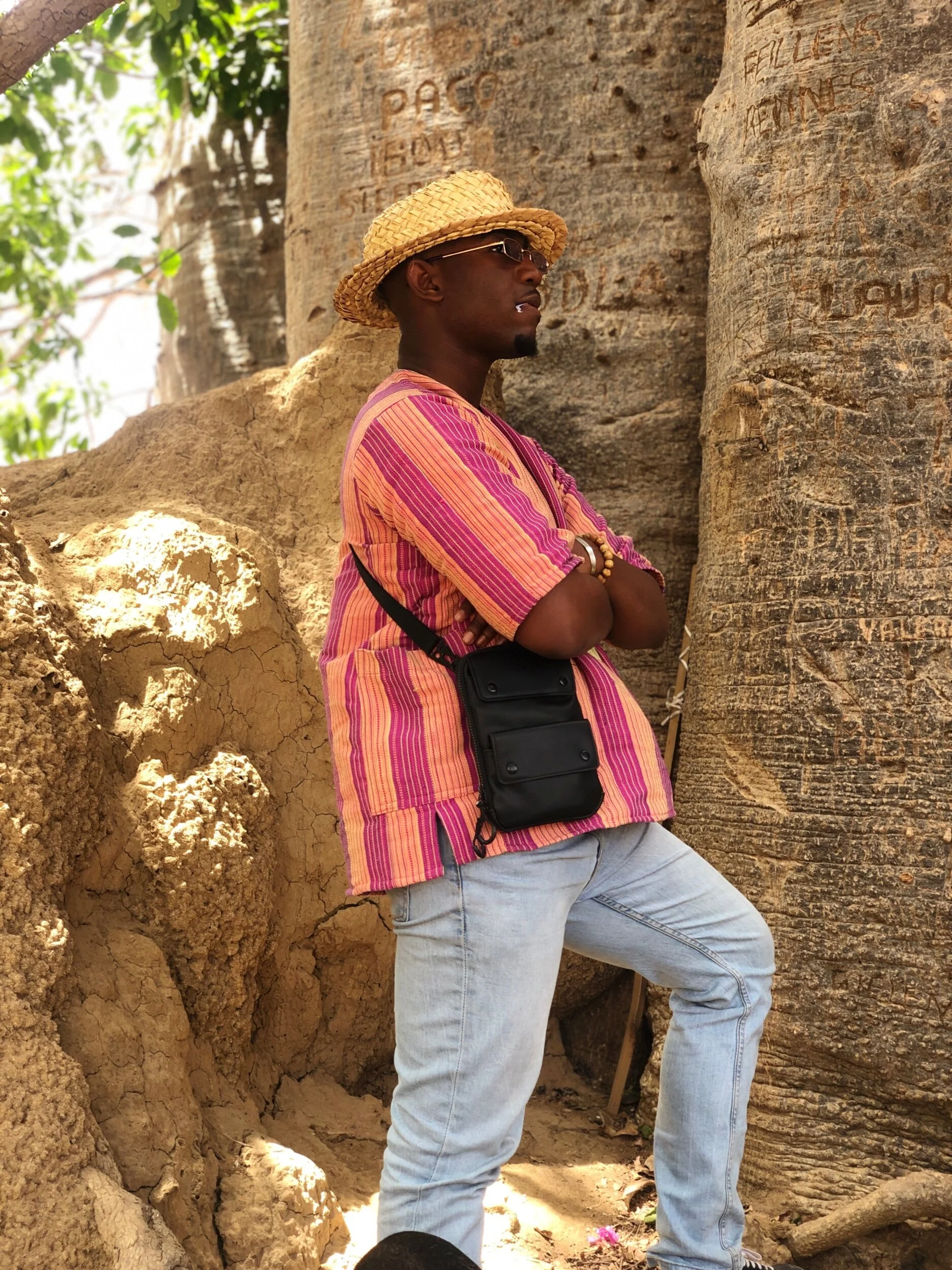

My friend Fatima, reflecting on the Christian and Muslim burial site

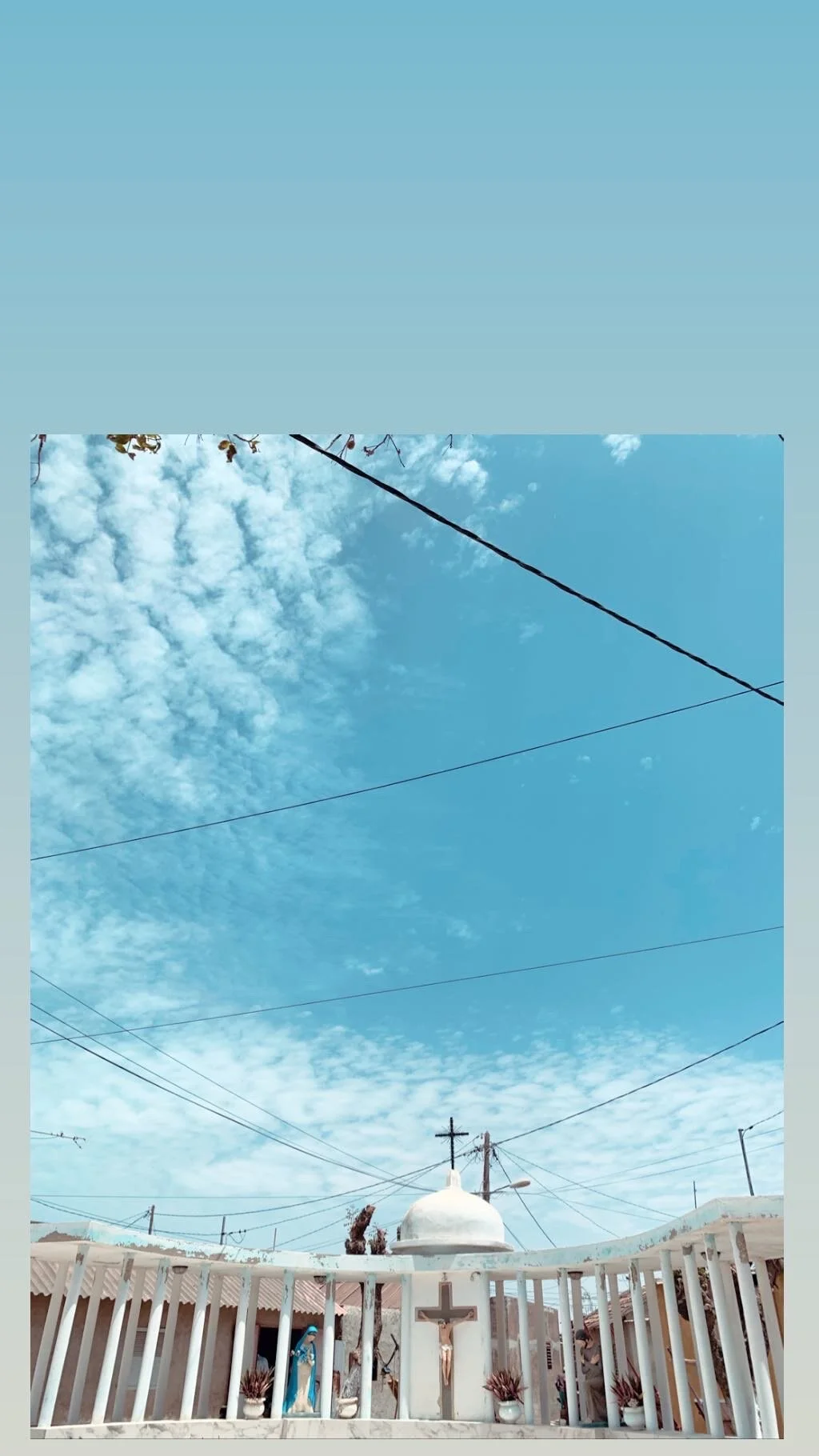

Edifice found in a public space, located very close to where the sacred Boab Tree is planted.

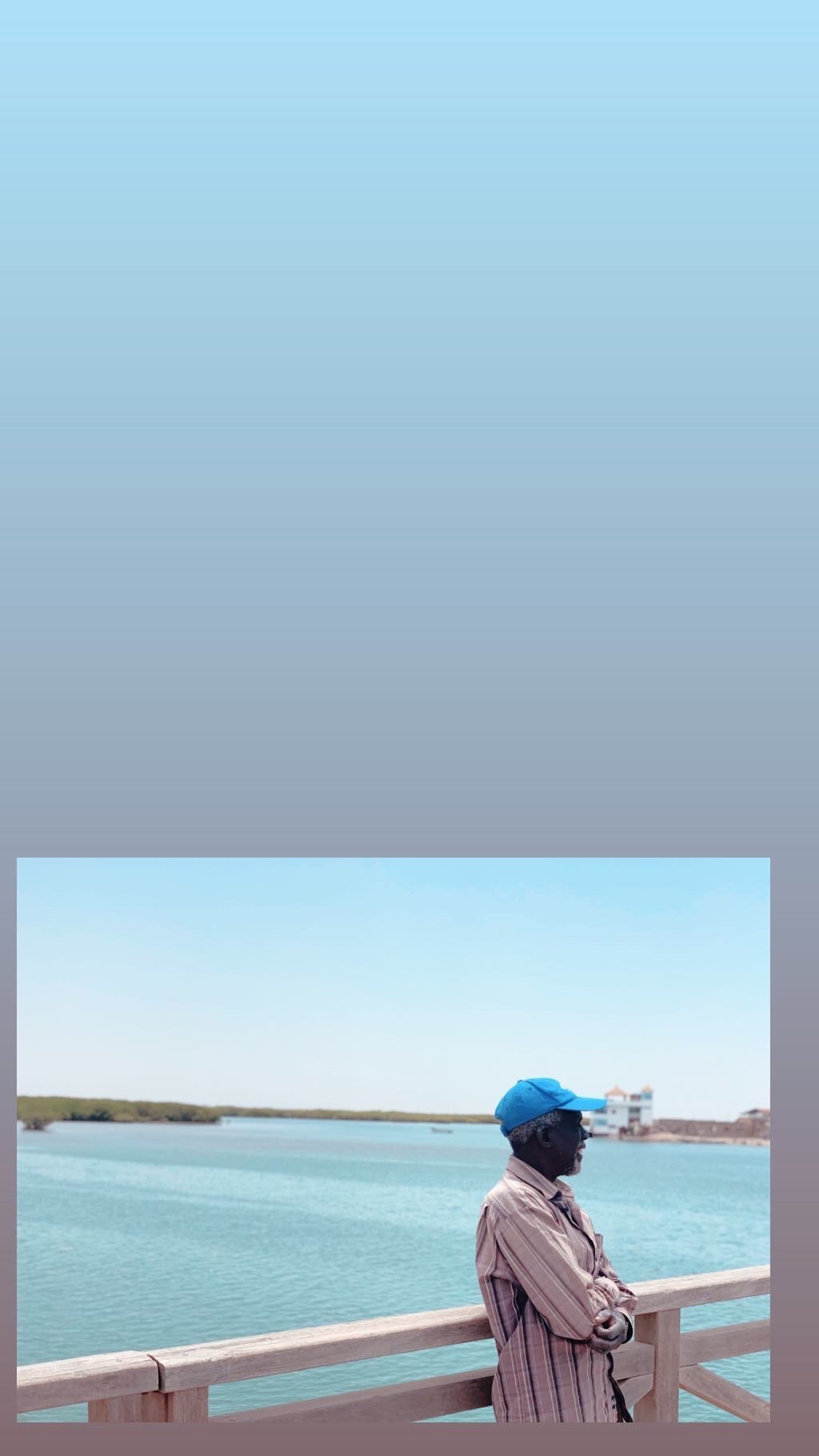

Local Joal community member comfortably relaxing on the bridge that is used to cross over to the Christian and Muslim Burial Grounds